Responsibility to Vote by Refusing to Vote: The Jeju 4.3 Incident

- periginal

- Aug 4

- 13 min read

Introduction

May 10th, 1948, the provisional government of Korea held its first democratic election in its multi-millennial history. For the first time, Koreans were electing their representatives. The nationwide turnout was over 95%. However, two districts on the island of Jeju had voter turnouts of below 50%, discrediting the election to United Nations (UN).

The massive voter boycott in these districts is usually consider the outcome of the ‘4.3 Incident’, an attack on 12 police-boxes by communists on April 3rd, 1947. In retaliation the US Army military government in Korea (USAMGIK) and police suppressed communist uprisings on the island. This campaign progressed through the Korean War and was only lifted in 1954 after the death of 30,000 islanders and mass incarcerations. Framing the police-box attack as the origin of the ensuing 7 years of massacre overshadows the fact that majority of the general population in the districts refused to vote.

The right to vote is an expression of sovereignty for the people, through which they determine their own future. Usually, the fight to attain the right to vote was the focus of attention, while the responsibility to vote is considered a civic duty than an enforceable law. But when elections are not democratic and choices do not represent the will of the people, is it in the spirit of democracy to comply and vote?

Governments and dictators attempting to legitimize themselves stage fake elections. Democracy becomes a mockery, and the vote is reduced to a rubber stamp. People have the right to vote, but also the right to refuse to participate in false elections.

Therefore, we must reassess the ‘Jeju 4.3 Incident’ as the election boycott which resulted in the massacre of 30,000 civilians over the course of 7 years. This paper aims to understand the refusal to vote, and how the Jeju people tried to protect democracy by denying an election that did not convey the will of the people.

Thesis

While the right to vote is a principle of democracy aimed to ensure that all voices are heard, the responsibility to vote is a fundamental principle to ensure that the will of the people is legitimately conveyed. When an election is designed to grant false legitimacy to tyranny, refusing to vote is the proper execution of responsibility. Therefore, the act by the Jeju people resisting a manipulative election is protecting democracy by ironically refusing the responsibility to vote.

Background

The USSR joined the war against Japan just days before the surrender. At the Moscow conference of December 1945, the US determined a “deadlock has developed with the Soviet representatives”. The Soviets already prepared to establish a “puppet government” in the north and prevented a nationwide election from taking place. To quickly establish a secure presence, the USAMGIK employed former Japanese collaborators to key positions in the police.

With the general concern that the nation would be split in two, a large-scale demonstration was held on March 1st, 1947. On Jeju Island, a mob was incited when a mounted police officer injured a bystanding boy. The police retaliated by firing at the crowd, killing six, including women and children. With no apology from the police, an island-wide strike began on March 10th, with 42,000 people and 166 organizations participating by the 13th. Determining that this was a communists plot to subvert the election, the police came down hard against the strike. Throughout 1947, mass arrests were made and civilians, including children, were tortured to death.

The negotiations between the US and USSR terminated by September 17th, 1947, and the US deferred to the UN to settle the matter of establishing a government in Korea. The UN temporary commission on Korea (UNTCOK) visited Korea in January of 1948, and by February, announced the May 10th election for a National Assembly. However, UNTCOK was barred from entering the North, which feared their lower population would establish a government weighing to the south.

The 4.3 Police-box Attacks

On April 3rd, 1948, Kim Dal-Sam he led 350 guerrilla fighters to attack 12 police-boxes across the island in order to disrupt the coming elections. The police and right-wing militia retaliated, isolating the guerrilla forces in the mountains.

The guerrilla forces were heavily influenced by the North, with their leader, Kim Dal-Sam, abandoning the island to fled to the North as a hero. The police and US forces were not blameless either, as they purged the mountain villages of potential communists. Even during peace talks with the guerrilla forces, an arson attack was staged, with disguised right-wing militia murdering the villagers and setting fire to the houses as a US Combat Camera Team filmed the supposed ‘communist attack’, which was later released as the documentary propaganda film ‘May Day’.

There were active communist influences aimed to disrupt the national election, but the total number of guerrillas was about 500 men armed with 30 rifles. While police and US military retaliations could be criticized as disproportionate, this was nothing compared to what was to come. In such light, we must consider the namesake 4.3 incident police-box assault as peripheral to the actual focus, the 5.10 election.

The 5.10 Elections

In South Korea 7,837,504 persons registered and 7,036,750 went to the polls (95.2%). However, in the two northern districts of Jeju 11,912 of 27,560 (43%) and 9,724 of 20,917 (46.5%) voted, as a large number of the population decided to boycott the election altogether.

UNTCOK deemed the partial outcome of the elections as insufficient. A declassified CIA report records that the UNTCOK “feel that since the assembly does not represent all of Korea, neither the assembly nor any government established by it can be designated as ‘national”.

The UNTCOK declared that the elections were undertaken under “a certain degree of restriction of freedom of voters”, and while adding, “the efficiency was so remarkable that the figure of voting reached a very high percentage in a few hours. This, in my mind, should give rise to a certain degree of caution and reservation.” However, Syngman Rhee protested the press release, and the statement was redacted, immediately.

Following the election, Military Governor Dean issued an executive order “By virtue of the power vested in me by Section 44, Law for the Election of Representatives of the Korean People”, stating that the results of the two districts be “null and void because voting was held in less than 50%” because of “activities and violence of subversive elements”, while an “election which truly represents the will of the people” will be “postponed for an indefinite period” until “a peaceful and undisturbed election” could be possible.

Colonel Rothwell Brown was appointed the military governor of Jeju on May 20th. The USAMGIK began suppression in preparation for the re-election. By May 23rd 3,126 arrests were made, but only 3 rifles were found. By the June 23rd re-election over 6,000 arrests were made, mainly civilians.

There is a sense of urgency for the elections. General MacArthur reports, “it is impossible to hold any elections. …. North Korea, which the communist stooges in South Korea will hold up to an ignorant people in South Korea as their ‘own democratic government established by the people themselves’, we may as well prepare for a great resurgence of communist influence …. any further delay in positive action in South Korea will be fatal.”

Scorched Earth

Following the official split between the North and South, US forces, retaining operational control of the South, moved to quell the communist uprising. The Korean government also saw the failed elections as active sabotage. “If we have to sacrifice 300,000 Jeju islanders to establish our republic, so be it.” Colonel Park Jin-Kyoung, commander of the 9th regiment, proclaimed as he intesified suppression against the perceived communist uprising. When Park was assassinated by sympathetic soldiers due to his reckless attack on civilians, Major Song Yo-chan succeeded to spearhead the suppression efforts.

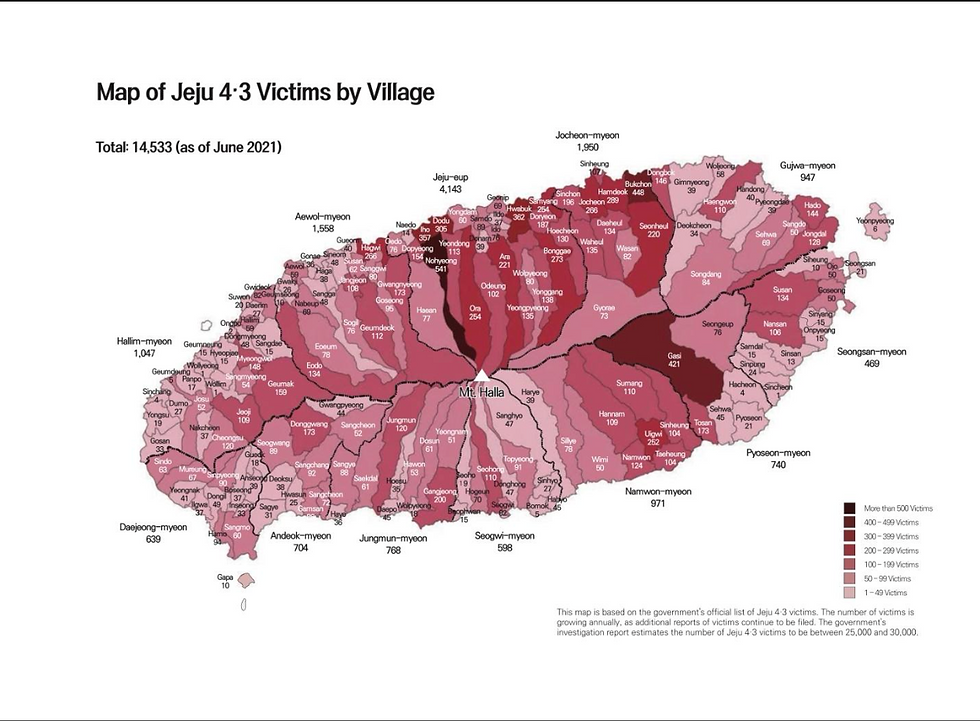

To eradicate the communists in the mountains, Song set up a boundary of 5 kilometres from the coastline, which consisted of 80% of the area of Jeju Island, and declared that anyone passing through be considered an insurgent. More than 100 villages were destroyed and 40,000 houses were burned. (See Appendix A, B) Livestock was slaughtered lest it provide sustenance for mountain dwellers. To date 10,715 bodies have been identified, 3,171 are still registered as missing, but these numbers are growing even today as new mass graves are being uncovered. (See Appendix C) As the Korean war broke out, the military, fearing insurgency in the prisons, executed a large number of detainees without trial. (See Appendix D) Over the course of 7 years, from 1947 to 1954, an estimated 25,000 to 30,000 casualties occurred.

On October 31st, 2003, President Roh Moo-hyun apologized on behalf of the government. Since 2018 retrials of the prisoners who had been arrested for refusing to vote and fled to the mountain were conducted and exonerated. Most were farmers, students, and housewives. During the 2024 Jeju Peace Forum, Robert Gallucci of Georgetown University said, “Reparations of the past are being made, even in the US. What Jeju 4.3. needs is the world to know what happened to redress the wrongs.” (See Appendix E)

Voting as a Responsibility

Democracy remains fragile. When democracy cannot protect us, it is our duty to defend it. The right to vote reminds us that sovereignty lies in its people. Voting as a responsibility function to legitimize the elected, allowing them to represent the people. But if the election itself does not reflect the will of the people, do they not have the responsibility to refuse this imitation of democracy?

When an election aims to legitimize the will of the government over the people it lays the foundation for tyranny. Vladimir Putin retained his presidency in an election where he gained 87 percent of the vote, from a 77 percent turn out. The new electronic voting system aided in the government to “manage” votes. Overseas exit polls indicated most were against Putin, but were intentionally invalidated. In Syria, Assad turned the ballot into a rubber stamp to legitimize his tyranny. Boycotts against the election typical occurred in non-regime territories.

In Korea, it wasn’t until 1987 that the presidential elections returned to the public, almost 40 years since the 4.3 Incident. While we cannot blame every fraudulent election on the 4.3 Incident, it created a precedent, allowing politicians to liberally manipulate the elections for their own purposes.

“In all states and conditions, the true remedy of force without authority is to oppose force to it.” Being forced to choose an inevitable future, the people of Jeju Island chose to practice their democratic responsibility to vote through resistance.

Appendix A

Victims of the massacre were usually refugees, rarely armed, hiding in the mountain villages.

“Before a rebel slaughter as the rebellion began. An American adviser, Lieut. Ralph Bliss, looks on silently where no advice will help.” LIFE Magazine, 15 November 1948. Ben Davenport, “Commemorating South Korea’s Cheju April 3rd Incident: Cultural Trauma and the Politics of Postmemory,” Cambridge Heritage Research Centre. https://www.heritage.arch.cam.ac.uk/publications/spotlight-on/cheju.

Appendix B

Massacres wiped out entire villages, mostly in the mountain villages.

Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation, “Map of Jeju victims by village”, What Is the Jeju April 3rd Uprising and Massacre? - From Truth to Peace Jeju 4·3, 2018. http://jeju43peace.org/historytruth/archives/what-is-the-jeju-april-3rd-uprising-and-massacre/.

Appendix C

Excavation site under Jeju Airport runway where 237 bodies were uncovered.

Bloody history buried under Jeju International Airport. Jeju Weekly. 26 March 2011. http://m.jejuweekly.net/news/articleView.html?idxno=1383

Appendix D

Prisoners incarcerated without trial were executed once the Korean War broke out.

Jeju inhabitants awaiting execution, 1948, World History Archive. https://www.united-archives.de/id/02733520

Annotated Bibliography

Primary Sources

Government Communications

Hodge, John R, “Military Governor Dean’s executive order”, June 12 1948, Telegram 501.BB-Korea/6-1248 to the State Department, Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea. https://db.history.go.kr:443/id/ps_003_0280.

The Commanding General of the US forces in Korea informs the State Department of Military Governor Dean’s executive order following the May 10th election and the UNTCOK report, which shows the low voter turnout in Jeju island. I used this document, because the exact executive orders were necessary, as the actual Election law does not specify a necessary voter turnout threshold and that the decision to invallidate the election was due to concerns of legitmacy.

MacArthur, Douglas, “Menon's report to UN interim assembly”, 22 February 1948, Telegram 501.BB-Korea/2-2248 to George C Marshall, Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea. https://db.history.go.kr:443/id/ps_001_1850.

MacArthur raises his concern for communist activity in his telegram to Marshall. I used this communication to show that, following the failed elections, the US would pivot strongly to suppression.

Marshall, George C, “Establishment of a puppet government in North Korea”, Telegram 501.BB-Korea/2-1848 to to Reginald P Mitchell, 18 February, 1948, Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea. https://db.history.go.kr:443/id/ps_001_1670.

Telegram from George Marshall, Secretary of State to Reginald P Mitchell, the Political Advisor in Korea, voicing his opinion that USSR has established a puppet government in the North and will also influence communists in the South. I used this telegram to convey what the US determined of the overall situation in Korea was.

Marshall, George C, “Refusal of Soviet government to permit UN Commission to enter North Korea”, Telegram 501.BB-Korea/1-2948 to Reginald P Mitchell, 29 January, 1948, Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea. https://db.history.go.kr:443/id/ps_001_1100.

Marshall writes to the political advisor that the North is not cooperating with the UN Resolutions of November 1947. I used this communication to show how the US and USSR were inevitably moving towards establishing separate governments in Korea, despite UNTCOK oversight.

UNTCOK, Press Release No. 59 - Press Statement by Yashin Mughir, Syria, 13 May 1948, Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea. https://db.history.go.kr/id/pu_002_1320.

Syrian delegate of the UNTCOK, Yashin Mughir suddenly announced how he felt the May 10th elections were being forcefully executed. It was a sudden press release, which was immediately countered.

UNTCOK, Press Release No. 63 – Redaction of Press Statement by Yashin Mughir, Syria, 14 May 1948. Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea . https://db.history.go.kr:443/id/pu_002_1340.

Yashin Mughir’s statement was immediately withdrawn the very next day, and he expresses how it was his “personal” opinion, and not that of the UNTCOK.

I used this to show that the US and South Korean government both moved to silence questions of legitimacy to the election.

Vincent, J.C.. “Basic Issue on which U.S.-U.S.S.R. Joint Commission in Korea is Deadlocked”, Telegram 501.BB-Korea/4-1246 to the Secretary of State. April 12 1946. Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea. https://db.history.go.kr:443/id/ps_001_0030.

The telegram to George C Marshall, Secretary of State. I used this communication to represent what the US government determined of the outcome of the US-USSR joint commission.

Interview

Gallucci, Robert, Interview with author, May 30 2024.

I interviewed Robert Gallucci before and after his panel at the Jeju Peace Forum in 2024. At the forum Gallucci was a panel for the Jeju 4.3. In the interview, he proposed practical steps in which a modern resolution of a historical tragedy could be formed.

Secondary Sources

Books

Bruce Cummings, The Origin of the Korean War: Liberation and the Emergence of Separate Regime, 1945-1947, New Jersey, Princeton University, 1981.

Bruce Cummings is a scholar on Korean History. I used his book to show how the provisional South Korean goveernment inherited the Japanese collaborators, thus planting the seed for police-civilian resentment.

History of the United States Army Forces in Korea, Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea. https://db.history.go.kr:443/id/husa_003_0040_0030_0090.

This is the archived written history of the activities of the US forces in Korea at the time. I used the data to present appointments of key personnel and results of the island wide arrests.

The Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation, The Jeju 4.3 Incident Investigation Report, The Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation, Jeju, Korea, 2003. http://43archives.or.kr/data/publication/list.do.

The government-initiated Jeju 4.3 Incident Investigation Report was initiated following the presidential apology in 2003. It contains collected resources from testimonies and written histories. I used it to collect data on activities of the Korean Police and Constabulatory.

Locke, John, “Second Treatise of Government”, 1680.

I quoted John Locke to present the right to rebellion against tyranny.

Journal Articles

Merrill, John, “The Cheju-do Rebellion,” Journal of Korean Studies, Vol. 2, 1980.

The Journal discusses the Ora-ri arson incident which was captured by the US army film crew and turned into a documentary film. The silent documentary itself is available to view in video archives, but does not supply analysis where investigation reveals how the arson and murders were staged. Therefore, I used the journal to comment on this incident.

Yamamoto, Eric K. & Burns, Suhyeon, “Apology & Reparation: The Jeju Tragedy Retrials and the Japanese American Coram Nobis Cases as Catalysts for Reparative Justice”, 45 University of Hawaii Law review. 5, 2022. https://hdl.handle.net/10125/105168.

The Law review details the outcome of several retrials where it was shown that prisoners were not given a trial, incarcerated, then executed. I used this to show the victims of the massacre were innocent civillians.

Internet Articles

Haid Haid, "The Illusion of Legitimacy: Unveiling Syria’s Sham Elections." Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank, 16 July 2024. https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/07/illusion-legitimacy-unveiling-syrias-sham-elections.

Non-scholar article online, showing how Syria also used election control to suppress dissident voices and legitimized tyranny.

Zavadskaya, Margarita, “Why Does the Kremlin Bother Holding Sham Elections?” Journal of Democracy, March 19 2024. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/elections/why-does-the-kremlin-bother-holding-sham-elections/.

Non-scholar article online, comparing Putin’s reelection campaign with tyrannical election fraud. I used this article to show how elections are used to legitimize government in modern day.

Government Report

Intelligence highlights No.5. Week of 8 June - 14 June, 1948, Office Reports and Estimates, CIA, Far East/Pacific Branch, 14 June 1948, Freedom of Information Act Electronic Reading Room. https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/home, CIA-RDP79-01082A000100010016-2.

The declassified report following the May 10th election reports collectively show the opinion expressed by UNTCOK, and the assessment of the US government on the UNTCOK’s position. I used this report to show that the US did not trust UNTCOK to fulfill its mission.

Weckerling, John, “Report of U.S. Liaison Officer with the UN Temporary Commission on Korea (UNTCOK)”, Report to the Commanding General of USAFIK, 1948, Database of Contemporary Korean History, National Institute of Korean History, Gwacheon, Korea, 1948. https://db.history.go.kr:443/id/pu_001_0010.

The report of the US Liaison Officer with UNTCOK, John Weckerling, to the Commanding General of the US Armed Forces in Korea. I used it to collect official data on the 5.10 Elections.

Appendix Graphics

Davenport, Ben. “Commemorating South Korea’s Cheju April 3rd Incident: Cultural Trauma and the Politics of Postmemory,” Cambridge Heritage Research Centre. https://www.heritage.arch.cam.ac.uk/publications/spotlight-on/cheju.

Very few pictures of actual casualties during the massacre remain. The photograph published in LIFE magazine could not be found in the magazine’s archives, and only secondary sources remain. I used the photo to show the military presence, US involvement and civilian tragedies at the same time.

Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation, “Map of Jeju victims by village”, What Is the Jeju April 3rd Uprising and Massacre? - From Truth to Peace Jeju 4·3, 2018. http://jeju43peace.org/historytruth/archives/what-is-the-jeju-april-3rd-uprising-and-massacre/.

The map in only printed in a booklet that is offered at the Jeju 4.3 museum. It shows the distribution of victims. I wanted to show that the massacres were island-wide, with significant casualties where entire villages disappeared.

Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation. “Bloody history buried under Jeju International Airport”. Jeju Weekly. 26 March 2011. http://m.jejuweekly.net/news/articleView.html?idxno=1383

The online newspaper article provides a picture of a modern uncovering of mass graves beneath the Jeju airport runway. I wanted to show that despite the lack of photos of the period depicting the massacres, there are plenty of plenty of bodies to present.

World History Archive, “Jeju inhabitants awaiting execution”, late 1948, World History Archive. https://www.united-archives.de/id/02733520.

This is a rare photo that remains of the prisoners awaiting execution. I wanted to put a face on the victims.

Comments